Bill Brandt — Stones & Curves

Bill Brandt’s nudes live at the junction where geology and the body become a single grammar: pebbles answer knees, cliffs echo shoulders, the human silhouette reduced and enlarged into an architecture of contour. Stones & Curves gathers twelve iconic prints — vintage gelatin-silver impressions hand-made by Brandt in the 1970s and entering this presentation with provenance from Marlborough Gallery — to consider a practice where form, not titillation, is the subject.

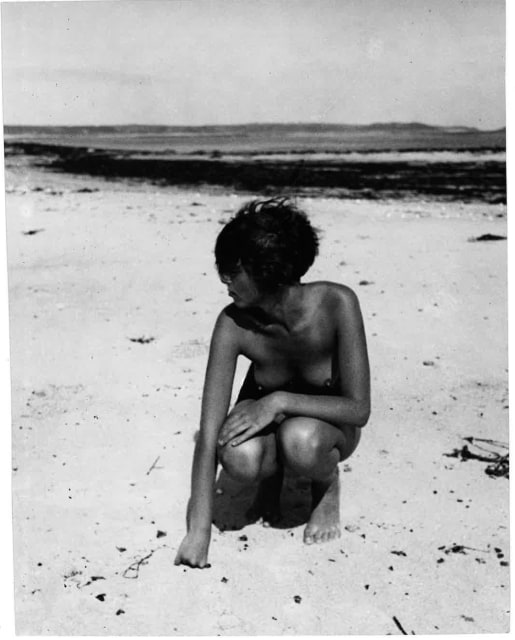

At the centre of the selection sits one of his earliest beach photographs, Nude, Scilly Isles, 1934 — This photograph is the beginning before he pushes perspectives. This body of work, from here on, refuses to be only a nude, instead thinking itself as landscape, as folded mass and negative space. The beach works, taken across England and the French coast, show bodies embedded in terrain so that limb and rock read as mutual sculpture rather than as object and spectacle.

This transformation is technical as well as conceptual. Brandt’s later use of a super-wide Hasselblad and wide-angle optics — and his willingness to bring the camera extremely close to his sitters — produces perspective compression and elongation that render flesh like worked stone: knees become promontories, backs become ridgelines. The camera does not flatter; it re-maps. That formal rigour is inseparable from Brandt’s lineage of modernism — the affinities with Moore, Picasso and the École de Paris are visible in how bodies are abstracted into volumetric, biomorphic forms.

Brandt problematises the straight line between spectator and spectacle — between subject and object — that so many classical nudes assume. Critical voices have argued that his pictures “problematize the relation between photographic subject and photographed object,” making the body an active field of form rather than a passive site of desire. Cambridge University Press & AssessmentThe Museum of Modern Art

Seen together, these twelve prints operate as a small manifesto. They insist that the nude can be an exercise in tectonics and tenderness, that erotic charge need not be synonymous with objectification, and that a photograph can be at once sensual and formally austere. Brandt’s late-print vintages — produced when the artist revisited and authorised larger impressions of these earlier images — therefore bear two histories at once: the moment of capture on a windswept shore, and the later, deliberate act of presentation and edition.

We invite the viewer to move slowly: to let a knee read as stone, a shoulder as a slope, and in that translation to hear how Brandt quiets the conventions of the erotic photograph. In Stones & Curves the beach is not a backdrop but a collaborator; the body is not an object but a form thinking itself into being.